Money Laundering Compliance for Non-Financial Entities: New Rules and Old Issues

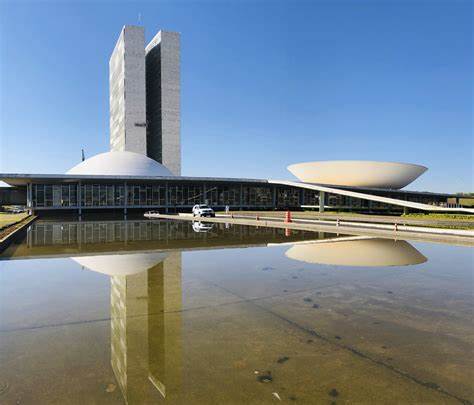

Money laundering is a burning issue in Brazil that has attracted attention of legislators and law enforcers alike as a response to much publicized political scandals. In spite of the fact that some of the most serious issues have arisen in the public sector, changes and controls brought by recent legislative changes (Law No. 12,683, dated July 9, 2012) introduced additional money laundering control obligations on private non-financial entities.

The Brazilian legal framework against money laundering, as created by Law No. 9,613, dated March 3, 1998, has two segments: the first defines hiding or investment in business of proceeds of crime as independent criminal offenses; and the second imposes recording and reporting obligations on certain business entities to enable detection of the crimes previously defined.

The list of entities that should be subject to the recording and reporting obligations has been extended beyond the original realm of financial institutions, entities with activities similar to financial institutions and luxury goods sellers. It now includes: i) consultants in real estate, corporate and financial operations, including legal consultants; ii) parties involved in the promotion, intermediation, negotiation or management of professional athletes and artists; and iii) parties involved in the sale of goods of animal or agricultural origin.

Even more importantly, any businesses that sell high-value goods and those that promote, develop or sell real estate have traditionally been part of the list, even before the amendments, and so continue. The concept of high-value goods is not defined and would be wide enough to cover capital goods and consumer goods of average or high value such as cars, boats and airplanes, etc.

The practical result is that most industrial, commercial and even services business are now subject to the administrative provisions of Brazilian anti-money laundering laws.

Such provisions traditionally included active obligations of the businesses covered by the rules to register clients and suspicious transactions, reporting the latter to a control organ, COAF (Council for Control of Financial Activities). The changes recently enacted created three additional obligations: i) registration of the businesses with COAF in case they operate in sectors that have no special regulatory body; ii) formal declaration to COAF in case no suspicious transactions exist, which may give rise to charges of fraud or even participation in money-laundering crimes in case suspicious transactions are latter discovered to exist; and iii) to adopt anti-money laundering compliance programs and internal controls, proportional to the size and volume of operations, in the form determined by COAF or other competent authorities.

The definition of the characteristic of compliance programs is contained in Resolution COAF No. 20, dated August 29, 2012, effective as of March 1, 2013. Such programs should foresee procedures and standards for the identification of clients, business relationships, and suspicious operations, as well as foresee criteria for the classification of both clients and operations according to their risk level. The program should be formally approved by the chief executive officer in charge of the business and provide for training and monitoring of employees. It should also foresee mechanisms to eliminate conflicts with business interests of the organization that might otherwise impair the application of the programs.

Failure to create a compliance program is an administrative offense punishable with penalties ranging from fines up to R$ 20 million (roughly US$10 million) to temporary or permanent closure of business. The lack of a program is not by itself a criminal offense, but it may, depending on surrounding circumstances, be considered as willful blindness in case actual money laundering occurs, entailing criminal persecution.

The regulations in force impose stringent obligations on business not normally exposed to the culture of financial compliance. Swift adaptation is nonetheless advisable, since the Brazilian stage of institutional development features stern exemplary cases of punishment to atone for generally lax supervision.