All changes discussed in this issue of LS Brazil Outlook have been instituted by provisional measures, or MPs (“medidas provisórias”). Under Brazil’s Constitution, MPs are instruments that have the status of ordinary legislation and are submitted by the Executive to Congress but which nevertheless take effect instantly, upon publication in the Official Gazzette.

All changes discussed in this issue of LS Brazil Outlook have been instituted by provisional measures, or MPs (“medidas provisórias”). Under Brazil’s Constitution, MPs are instruments that have the status of ordinary legislation and are submitted by the Executive to Congress but which nevertheless take effect instantly, upon publication in the Official Gazzette.

Since the beginning of president Jair Bolsonaro’s administration in January, there have been nine MPs that lost effect after four months as they were not confirmed by Congress. So, what happens to transactions that take place based on provisions of an MP that is subsequently rejected, or not examined in a timely manner, in Congress?

Some background is warranted.

MPs are meant to be issued by the Executive only in case of relevance and urgency, but they have proven to be the most relevant means for enacting law and implementing public policy in all areas of government and are routinely resorted to. Literally thousands of MPs were enacted from 1988 (when they were created under the then new Constitution) to 2001. In reaction to what was perceived as an excessive, even abusive, use of MPs by the government, in that year Congress approved a constitutional amendment to impose substantive restrictions and procedural rules regarding MPs.

Since then, a wide array of matters can no longer be addressed by MPS, which include political rights, criminal and criminal procedural law, and the organization of the Judiciary. As for procedure, Parliament ought to amend, reject or accept a provisional measure within 60 days (renewable once, automatically); also, and importantly, MPs no longer can be re-issued if not reviewed by Parliament within the prescribed deadline.

A decision adopted in 2015 by the Supreme Court imposed further constraints on the use of MPs. It prohibited amendments that are unrelated to the original subject matter of the MP at hand (yes – it was extremely common for a Member of Congress to write totally unrelated amendments into an MP in order to benefit from its fast-track procedure; attempts to do so are still common, but more easily barred given the direct prohibition under the referred Supreme Court decision).

The number of MPs issued since the referred 2001 constitutional amendment dropped dramatically, but MPs remain a central feature of lawmaking in Brazil, both in terms of their number and the range of matters they address.

What about acts and facts having taken place under the provisions of a defunct MP – one not reviewed or approved in Congress within the 120-day deadline?

Under paragraph 3 of Article 62 of the Federal Constitution, should Congress fail to approve a given MP within the referred deadline, the MP at hand will lose legal effects from the date of its issuance (ex tunc, in legal parlance). This provision goes on to say that should this occur Congress shall issue a decree governing the legal relationships deriving from such MP.

However, what if Congress fails to issue such legislative decree? Paragraph 11 of Article 62 then comes into play. It provides that when Congress fails to issue this legislative decree within 60 days (counted from the date the MP was rejected or from the date the 120-day deadline elapses, as the case may be), the legal relations that may have been created while the relevant MP was in force shall remain in place.

This is indeed what happens in the vast majority of cases, as Congress rarely issues such legislative decrees. The end result is that whatever happens – legally speaking – while an MP was in force almost invariably remains in place. This is, needless to say, a matter of high practical (and legal) relevance for anyone contemplating initiatives predicated upon provisions of a medida provisória.

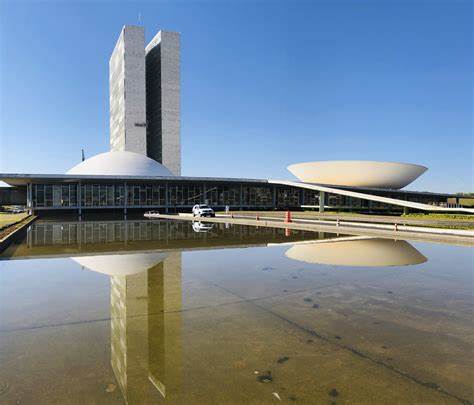

Image credit: Leonardo Sá/Agência Brasil

Felipe de Paula

Partner, XVV Advogados

Bolívar Moura Rocha

Partner, Levy & Salomão Advogados